Getting unstuck from blood diamonds

I hurt my back pretty badly last year. To recover, I’ve had to change a lot of my behaviors and create a number of new rituals. One is a weekly four mile walk, split in the middle by a nice bowl of soup at Wagamama. Always the same route, always the same soup, always with my notebook so I can do some writing.

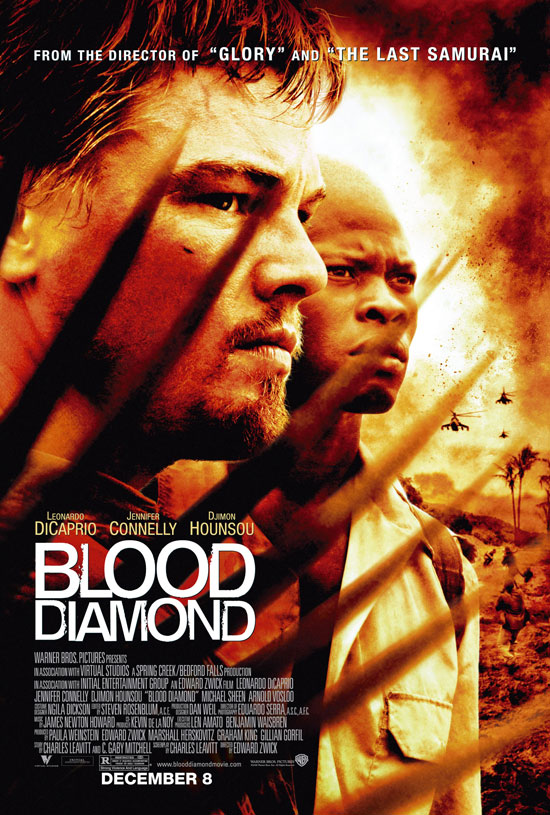

Tonight, as I was eating my chicken itame, I was writing about how we become unstuck. A simple concept, but something that’s not easy to do. As I began to write, I could hear two women at the next table discussing blood diamonds. One woman was explaining the idea to the other, and doing a good job of it, too. And it reminded me of seeing the movie Blood Diamond five years ago. If you haven’t seen it, this is a fine piece of propaganda – and I mean that as high praise. This is not a movie review, though, so I’ll leave it at this: I remember leaving the theater feeling stunned at the scope and tragedy of the problem.

Which is not unlike being stuck: to be stunned is to see the problem but be unable to see how our behavior could change to solve it. One of the biggest challenges in changing a bad behavior is having a good alternative behavior to replace it. We can’t just walk away from something - we have to be walking toward something, too. And usually, we get stuck because we don’t have a clear idea of what that something looks and feels like. This is not unreasonable - we don’t jump into the abyss based on the hope that there will be a soft landing because, generally, there isn’t.

The problem of blood diamonds illustrates how far we will go to remain stuck. While there is some disagreement about how many diamonds for sale these days should be classified as blood diamonds or conflict diamonds (diamonds which are sold to fund violence) the classification itself hides the fact that diamond mines themselves are violent and dangerous places. And once they are mined, diamonds must be processed, often by child laborers working for little pay in horrible conditions.

And we know this. At least, a lot of us do. Certainly the tens of millions of people who saw Blood Diamond have a fairly good idea that the diamond industry is responsible for massive human suffering. But have you noticed a sharp drop in the number of engagement rings you see in the last five years?

We might expect people to walk away from a product that has a detractor as popular as Leonardo DiCaprio. After all, the alternative to buying a diamond ring seems obvious: not buying one. But it’s not that simple. Diamonds, despite some bad PR, are a meaningful part of our culture. They’re not just beautiful stones, they’re a symbol of commitment and love that is immediately understood by just about everyone. That, in itself, is extraordinarily valuable, to people, as much as it is to DeBeers.

So, we are stuck, as a society, repeating a behavior that a growing number of us know is causing harm to huge numbers of people. The key to solving this problem would be to get past the idea that public awareness, in itself, is the solution. It’s not that awareness isn’t necessary or helpful, but it’s not enough. To change things, we’d need a new ritual with the potential to become meaningful to a critical mass of people. That is a tall order, because we can’t know in advance exactly what that ritual could be. But we can make informed guesses based on similar situations, try them out, and then nurture the ones that look like they have potential to mature into widely-practiced meaningful behaviors.

The actual development of a new meaningful behavior takes time, and we can’t know where we’ll wind up at the end of the process without going through the process. But there are signposts that point to possible areas to explore – hunches based on behaviors that are either directly or tangentially related.

For example, two of the Action Mill’s closest friends (they actually met while volunteering on one of our projects) recently exchanged rings as a symbol of their commitment to each other. But these weren’t just any rings. On a cold morning this past January, they went to a local art studio, took a class in ring making, and in a few hours they learned enough to forge simple, beautiful bands of silver for each other. This has the makings of a replacement ritual – the exchange of rings that are valuable because of their personal, touching origin story. And while classes like this aren’t ubiquitous, there are enough of them to start a trend – one with a great narrative and tangible artifacts that can be shared and understood in a short conversation. You’d be hard pressed to find someone that didn’t think this was a meaningful act.

Or, there’s a story I heard recently at a Cognitive Edge training, where one of the trainers showed us his Iron Ring - not a symbol of love, but still a great story with a moving ritual. Iron Rings are worn by many Canadian engineers as a symbol of their profession. While it’s a myth, the origin story is moving: the rings were first made from the iron of a collapsed bridge as a reminder of the obligation that engineers have to build safe, secure structures. And the rings have an advantage over diamond rings: they evolve over time, showing tangible evidence of their owner’s experience. The ritual – created by the author Rudyard Kipling – holds that the rings are to be made of rough metal and worn on the little finger of the dominant hand. Until the advent of computers, this meant that the rings would drag across the plans and papers that an engineer was working on, leaving marks, but also slowly buffing them smooth, so you can tell how experienced an engineer is by how smooth her ring has become. Can you imagine a more elegant symbol of longevity, experience and dedication?

Of course, an alternative symbol for engagement doesn’t need to be a ring at all, but both of these simple ideas illustrate that a meaningful replacement is possible. Whether either could point the way toward a behavioral change that would be widespread enough to end, or at least decrease, the suffering caused by the diamond industry is impossible to know without a concerted effort to prototype and test meaningful actions that could replace diamond rings.

Which is what getting unstuck is all about – not just moving, but moving in a better direction.

- Nick Jehlen's blog

- Log in to post comments