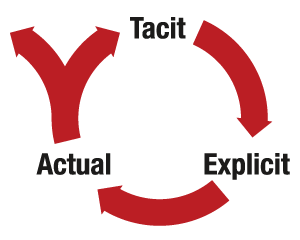

The TEA Cycle

A model for conveying understanding through new behaviors

There are several names for the kinds of problems we work on – intractable problems, wicked problems, social messes – which are all ways of describing problems in systems that are complex, changing and unpredictable. Health care in the US, for example, and global climate change, but also neighborhood development and organizational crisis.

These are problems that are hard to understand and analyse, and there are no right or wrong answers – only better or worse outcomes. They are resistant to traditional problem-solving techniques because they are unlike traditional problems; they are not puzzles with a limited and knowable set of possible solutions.

But they are not impossible problems, and there are a variety of methods and models have been developed to help us intervene effectively in complex systems. In our work, we borrow and adapt methods from many different disciplines, from military strategy to software development. And we develop our own as well, drawing on cognitive psychology and epistemology, but just as importantly on our own experiences.

One tool that we’ve developed is the TEA (Tacit, Explicit, Actual) Cycle, which we use to help us make sense of and navigate complex problems. (The TEA Cycle rests heavily on the work of Michael Polanyi, particularly his books The Tacit Dimension and Meaning.)

Tacit

There is no first step in a cycle, but we usually begin our work by addressing the Tacit domain. Polanyi developed the idea of tacit knowledge – knowledge that cannot be fully explained, and can only be acquired through practice and experience. For example, no matter how complete a set of bicycle riding instructions someone tries to write, it could never fully explain what you need to understand in order to actually ride a bike. You can learn to ride a bicycle only by riding one – through experience. In fact, most of our understanding of the world comes from this kind of experience – our interactions and behavior are the basis for what we know.

Tacit to explicit

Tacit is the realm of expertise and understanding, so we start by working with our clients and partners to understand what they understand – by making the tacit explicit. Since by definition tacit knowledge cannot be fully explained, we must accept some imperfection in this step. And trying to address it head on, by simply asking people to explain their own expertise, is rarely successful. But we’ve found that oblique methods that draw out narrative and use indirect inquiry can provide usable explicit knowledge. In other words, well-crafted exercises and questions can help people express what they actually know, rather than what they think they know.

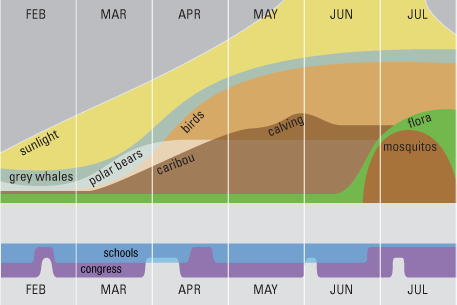

For example, when we began working with the Alaska Wilderness League, we started with an exercise developed by Cognitive Edge called The Future, Backwards, which helps surface a group’s basic beliefs about how the world works and what is possible and desirable. This generated a set of anecdotes about who the League is and what they believe. We also worked with them to create visualizations of the events that affect their work in order to discover previously unseen patterns.

Explicit to actual

We use this collection of explicit knowledge as the basis for the design of objects and systems which embody that knowledge – the actual step in our cycle. Because the knowledge that we’ve collected is complex and often contradictory, we start by designing many small, cheap prototypes so that we can quickly see how people react to them.

With the League, this meant that rather than meeting them at their offices for our second work session, we divided them into two groups and had them meet us at a coffee shop and on the National Mall, where we’d set up prototypes of activities that gave the staff a chance to interact with their own ideas and come to a deeper understanding of them. This interaction is behavior, which is the basis of tacit knowledge.

The value of deep understanding

We also created a visualization of the two kinds of systems that influence their work – the natural cycles of migration from the Arctic, and human schedules like legislative and school calendars. This is a good example of the indirect benefits of using the TEA Cycle – the clarity that arises from it is valuable for planning, decision making, creating internal alignment, and for external communication.

Actual to tacit: where understanding is conveyed

The next step of the cycle branches because actual experiences create two kinds of opportunities. First, when people interact with objects and systems that embody their own tacit knowledge it deepens their own understanding. And second, these objects and systems are entrance points that allow people outside the group to have direct experiences of the group’s ideas. In this way, understanding is both deepened within a group and conveyed to new people.

With the League, we developed two of the prototypes that provoked a strong reaction from the staff into kits that could be distributed to supporters and educators – the Arctic Gardens and the Arctic Kites. Because these objects were derived from the staff’s deep knowledge, they resonated with their constituents and helped them create meaningful interactions with their supporters.

This process also revealed a way for the League to re-frame its work – emphasizing the Arctic’s role as the birthplace to a huge range of animals, including birds that migrate to every US state and every continent before returning back to the arctic each year. This gave the League a powerful narrative to counter the impression that the Arctic is merely a barren icescape by showing that in fact it is the birthplace to an abundance of life, some of which winds up in our backyards each spring and fall.

The value of clarity

The clarity that comes from using the TEA Cycle creates deeper connections, broader alignment, and more effective communication internally and externally. Using the concrete actions, activities, and communications tools we developed, the League was able to reach new constituencies, achieve greater fundraising success with both large and small donors, and build closer ties with allied organizations that signed on to spread the campaign to their supporters, significantly extending their reach.

The TEA Cycle provides a framework for designing and testing more useful interventions in complex systems. Seeing the framework as a continuous cycle is essential, because any intervention in a complex system provokes change in that system, so successful interventions must be iterative. Because improved outcomes require large numbers of people to make fundamental changes to their understanding of and behavior within a complex system, it is important that interventions clearly and directly affect how people understand a problem and how they act. The TEA Cycle helps us design for both, in a generative process where understanding drives behavior, and behavior drives understanding.

- Nick Jehlen's blog

- Log in to post comments